Deep sky astrophotographers often resort to a “narrowband” filter (or line filter) to image deep sky objects when the Moon is up. This is because Moonlight scattered in the sky often washes out most color filters. However, when imaging emission nebula, we often will use a special filter that is sensitive only to a particular wavelength of light that is emitted by these narrowband targets. The most common is called “Hydrogen Alpha”, and it gives many nebula a bright pink/red appearance when photographed. This wavelength is not scattered in the sky by Moonlight and so you can do perfectly good “deep sky imaging” when the Moon is out. In fact, this particular wavelength is also great for light polluted areas.

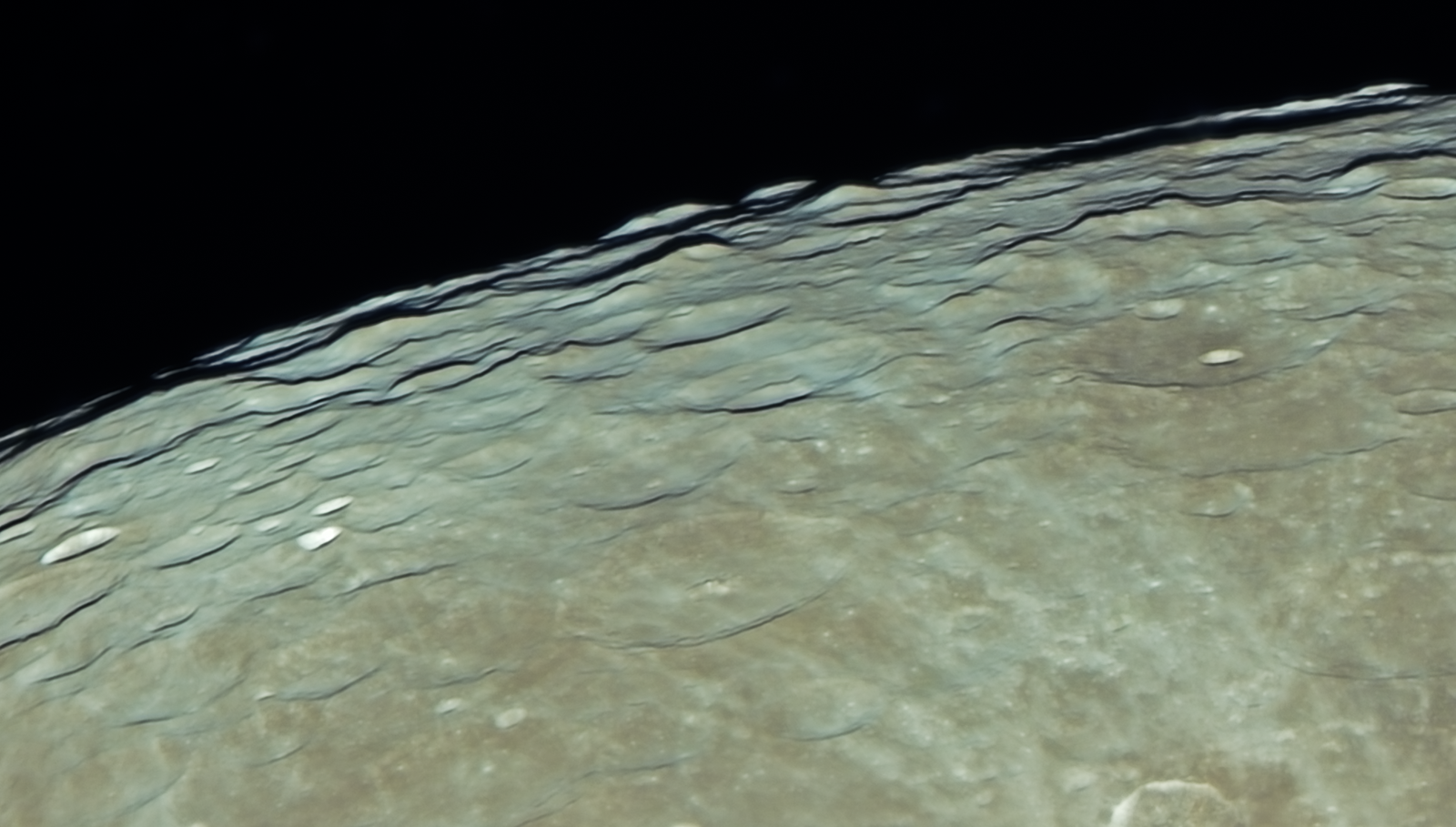

I love the Moon too though, and every time I find myself using one of these filters because the Moon is up, I also turn the camera towards the Moon for a shot. These kinds of filters produce a monochrome image, but that’s fine for the Moon. In addition, they are very much in the red end of the spectrum and these wavelengths are slightly less perturbed by a turbulent atmosphere, which can result in a sharper image.

Deep sky astrophotographers often resort to a “narrowband” filter (or line filter) to image deep sky objects when the Moon is up. This is because Moonlight scattered in the sky often washes out most color filters. However, when imaging emission nebula, we often will use a special filter that is sensitive only to a particular wavelength of light that is emitted by these narrowband targets. The most common is called “Hydrogen Alpha”, and it gives many nebula a bright pink/red appearance when photographed. This wavelength is not scattered in the sky by Moonlight and so you can do perfectly good “deep sky imaging” when the Moon is out. In fact, this particular wavelength is also great for light polluted areas.

I love the Moon too though, and every time I find myself using one of these filters because the Moon is up, I also turn the camera towards the Moon for a shot. These kinds of filters produce a monochrome image, but that’s fine for the Moon. In addition, they are very much in the red end of the spectrum and these wavelengths are slightly less perturbed by a turbulent atmosphere, which can result in a sharper image.

Deep sky astrophotographers often resort to a “narrowband” filter (or line filter) to image deep sky objects when the Moon is up. This is because Moonlight scattered in the sky often washes out most color filters. However, when imaging emission nebula, we often will use a special filter that is sensitive only to a particular wavelength of light that is emitted by these narrowband targets. The most common is called “Hydrogen Alpha”, and it gives many nebula a bright pink/red appearance when photographed. This wavelength is not scattered in the sky by Moonlight and so you can do perfectly good “deep sky imaging” when the Moon is out. In fact, this particular wavelength is also great for light polluted areas.

I love the Moon too though, and every time I find myself using one of these filters because the Moon is up, I also turn the camera towards the Moon for a shot. These kinds of filters produce a monochrome image, but that’s fine for the Moon. In addition, they are very much in the red end of the spectrum and these wavelengths are slightly less perturbed by a turbulent atmosphere, which can result in a sharper image.

The “Seeing” (amount of turbulence) was very good this evening (very still air), and I rather think I got an exceptionally sharp image of the Moon here. The only processing I did of this image off the camera was curves for tonal adjustments. I did no sharpening at all. The optic was a Sky-Watcher USA Esprit 150 with their 0.77 reducer. This is one of my top scopes and on this evening it did some of it’s best work under exceptionally good skies. The camera was a monochrome Player One Poseidon-M, and the filter was a Chroma 3nm Ha filter. The exposure time was 0.1 second.

Yes, I have some deep sky images from this evening too, but I’m still collecting light for those images before they are finalized.